VDG-Nachrichten 02/2020

The art of technical apparatus

It is rare to find glass apparatus maker who have achieved professional job security through a combination of art and technology in equal measure.

Bernd Weinmayer from the Tyrol in Austria is one of those who has achieved it. The trained glass apparatus maker reports how, some 30 years ago, guided by a clear vision, he set off on his rocky, adventurous path to independence, and how he discovered that the coronavirus does not necessarily mean the end. Motivating young glassblowers and business owners is very important to him, especially now, at a time when many small businesses are having their breath sucked out of them. Individuality, creativity, curiosity, and healthy degree of discomfort can survive many things

The editors asked me if I would like to write a report about my glass work for the VDG-News. Now, fast is not exactly my forte, but in the third week of the coronavirus lockdown in the Tyrol it seemed like a good opportunity to write something down about my professional career, perhaps with one or two tips on survival strategies. It is not easy for me to write a text about myself, because I do have many human weaknesses, but my professional pride and the self-confidence that comes from that are not small. Precisely this combination could make me come across as arrogant. On the other hand, I can imagine that especially young, prospective glassblowers could see my rather untypical career path as an option for their future too, choosing the sometimes hard and stony, but exciting path of starting their own company.

Why did I become a glassblower?

In 1988 I finished secondary school in Bad Aibling near Rosenheim, absolutely convinced that I did not want to go into a business. I’m not good at close professional contact with other people and an office job was also unthinkable. For want of an alternative, I decided to become a professional gardener. Shortly before starting work, my mother discovered that the only glass polytechnic school in Austria existed 20km away from our weekend house in Mariastein, in the Tyrol, Austria. She persuaded me to visit it, despite my rather reserved enthusiasm! In the grinding workshop it was noisy, in the glass-painting room it stank of solvents, and the students and teachers were so busy that I felt invisible. On the way back to the car park, we passed the door of the glassblowing workshop. That was nothing for me! Because I had heard that glassblowers don’t have a high life expectancy and I didn’t particularly want to die young. In front of the workshop door, standing outside, was an elderly gentleman who immediately spoke to me. He was the workshop manager of the apparatus glassblowing workshop. Without hesitating, he showed me around his kingdom. It looked like an oversized laboratory with a large coffee machine in the centre. There were about 10 pupils hanging around this centre, all seemingly very pleased because the teacher was taking a lot of time for me and the students got a free hour. In this hour I learned the story about Otto Schott, where in the world glass apparatus workers are in demand, and everything to the annual creative project work in the school, one month before Christmas. This meeting fundamentally changed my opinion about glassblowers. I realised that after about a year of training, glassblowing could open up a new, previously unknown world for me. Transparent glass, the most fascinating material par excellence, boundless in design and with little competition. People are familiar with drinking glasses, Christmas tree decorations or perhaps even laboratory glasses - but with an unbelievable number of other ideas made of glass, there is the unique opportunity to be to be the first to put this idea into practice. Many innovative glassblowers are globally networked and I had the feeling of having found a new family. That's how I still feel, to this day – endless opportunities and possibilities – with time being the only factor that renders specialisation all but a must.

Even during my schooltime, I received multiple orders which I completed in the shell of our weekend house with a minimum of tools. An American welding torch for 100,- DM, a pair of glasses, a coal plate and a used pottery kiln. Mass production kicked off with schnapps glasses and small bottle melts. After four years of technical school and two more years of further training in craft and design, I had so much work that I dared to become self-employed on leaving school in 1994.

Open to new ideas and change

Three years ago, after have produced more than 100,000 schnapps stamps, I handed over the orders for these to my professional "foster son" Patrik Winkler, who shares my almost all of my professional strengths and personal weaknesses. He is also able to successfully follow own his path as an independent one-man business. If you have developed a technique to a unique level, you will be discovered. And if, like me, you are rather shy of people and prefer to concentrate on production, then you can partner up with artists or companies that have already made a name for themselves or are perhaps already market leaders. The highest levels in particular must continuously reinvent themselves nowadays and can often be very grateful for creative input from outsiders.

It would be nice if it were a little more

The important thing here is not to sell yourself too cheaply. The basic prerequisite is always an absolutely brilliant, unique product. Then the price may "go through the roof", which arouses additional interest. At the end, there is enough of the cake left over for everyone involved and you are also doing your profession a great service, when it means that lamp-blown objects are achieving things that were previously only known from galleries for attractive studio glasses. The price bar is raised and this creates enough space below for other professional colleagues who may not yet have quite reached 100%. The crowning glory would of course be to raise the bar once again with even more fascinating glass works by other professional colleagues. It is important for the prices to continue to spiral upwards, because costs only move in this direction. Glass auctions can also increase the level of awareness. This happened in 2003, when plasma artist Ed Kirshner bought my 70cm tall "US Vampire" bottle at a GAS (GlassArtSociety) auction in Seattle.

This led to a friendship and a new staple, the plasma technique, which replaced my passion for melting bottles. For the last 15 years I have been trying to reach new limits with plasma neon technology. But all this without pressure and time pressure. All creative works, which can be seen on my website www.weinmayer.at, for example, have been made in my "spare time".

inside, 2018, collab mit daniel firman, 187cm, foto: christoph ascher

Last but not least, a good tip that I was given by Rudi Gritsch, a teacher at the glass school back then: look beyond the horizon and discover the truly flourishing areas of our profession. Most of them are young, open-minded movements that embrace collaboration and allow creative exchange and have recognized this openness as a survival strategy. Institutions like GAS (GlassArtSociety) and the VDG network can be very helpful in this respect.

By the way – it is a myth that glassblowers die earlier, being often confused with the profession of glassmaker. If the recommended occupational safety measures are taken seriously, I don’t see our occupational group as being particularly at risk. OK - the eyes are getting weaker, but that probably happens to most people over 40. And which profession is healthy? The joy of working hard and the ever-developing daily routine easily make up for these little aches and pains. So - keep hot and flame on!

Bernd

Strategy in a crisis

It has always been particularly important for me to be my own boss. I never wanted to be underestimated or certainly not permanently employed in simple tasks. Employment characterised by a lack of opportunities for further development and promotion. No, for me being employed was never an option! This was also the case with military service, which I would have had to do for Germany. I wanted to do everything I could to prevent my childish creativity and my easiness from being restricted by authority. So I registered my main residence as being in Mariastein, in my parents' holiday home, and turned my back on Germany, making me ‘unusable’ for the German army despite my positive call-up. Why do I mention this in this context? The individuality, the diversity and differences between people is what ensures maximum security in a crisis, as each person, in his or her natural, spiritual universe, finds solutions to the crisis. If this mentality were possible on a large scale, numerous of them would find themselves on the wrong track, but having a few allows strategies to be discovered which might be accepted by everyone else and so contribute to overcoming a crisis. However, we are living in an era of conformity and monopolisation. Life seems to hold few prospects for young people, even though the opportunities for education and career paths are easier and more diverse than ever before. So, have the courage to be independent. As your own boss, you decide what you do, how much you work and how much you want to earn. These are the preconditions for developing enormous capacity and for protecting yourself against burnout.

My career as a small business owner

The first years as an independent businessman in the handicraft sector were naturally hard. Every day I learned from my own mistakes and this process is still continuing today, after 30 years of professional experience. At some point one can feel the emergence of glass tension in the body, which ultimately determines success or failure. Just the thought that year after year you can improve your skills through practice gives you a lot of joy and strength for the future. What must a professional athlete think, who perhaps realises at the age of 30 that his body is actually past it?

And for me, especially in the early years, contact with other glassblowing companies was very important for finding out how a professionally equipped workshop should be set up and which basic techniques are essential for rational work. You should never believe that the techniques taught in the glass schools are really the be all and end all. All of my five greatest glassblowing idols (Kondo/Japan, Zinner/Lauscha, Salt, Eusheen and Buck/all USA) never attended a glass school but developed their own techniques autodidactically and perfected them to such an extent that they are currently the masters of their field. Glass schools are certainly a very good basis, but you will only stand out from the crowd if you have the courage to break new ground.

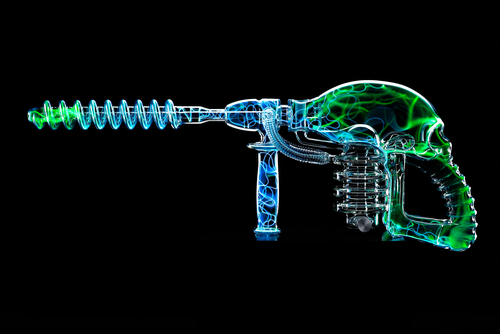

Due to a lack of orders, the first 5 years of my self-employment were filled with works which had been created in my mind and which represented the feasible limit for me at that time. This limit expanded from piece to piece. My former skulls and skeletons were often unsaleable and even today they can still by slow sellers. Nevertheless, the 101st skull will probably be better than the 100th. Practice makes perfect. My motivation is the realisation of ideas, some of which have been in my head for a long time, having to wait years until they are created, depending on their degree of difficulty. The combination of functionality and complex technical processes (plasma light), packed into a single fascinating design has been my main focus.

My daily business

This is and will remain solid glass apparatus in special niche areas, which finances the luxury of all these "hobby interests" for me. Meanwhile, the time spent on creative work has grown over 60%, creating a secure foundation based on several working techniques. Because one thing is clear - product life cycles are getting shorter and shorter and success this year is by no means a guarantee for success next year. In the past, large companies were guarantors of a secure job. Today, large employers are usually inflexible, very specialised and an employee is often an interchangeable number. But a good apparatus builder is not so easily replaceable and if he is successful as a flexible lone wolf, a corona crisis may temporarily push him into a ‘finder phase’ but will never make him unemployed. We produce endlessly durable reusable products and are therefore the perfect answer to questions about the climate and corona crisis.

70cm große „US-Vampire“-Flasche

ray hammer, 2012, collab mit roor, 70cm, foto christoph ascher

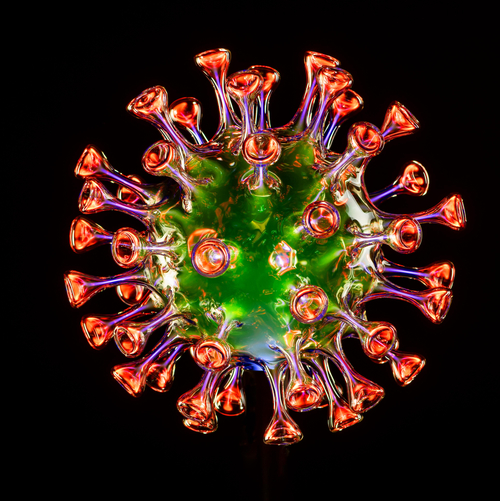

Covid Virus, gefertigt von Bernd Weinmayer. Fotonachweis: Christoph Ascher

Ian Barnes is the owner of the Englisch Institut in the Tyrol, Austria.

This article was translated into English by him, allowing it to be read in German and English on the website. We are grateful to Ian Barnes and Bernd Weinmayer for their contributions.

Read the article in german.

VDG-Nachrichten

Herausgeber

Verband Deutscher Glasbläser e.V., Karlstr. 7, D-48268 Greven

Erscheinungsweise

vierteljährlich im März, Juni, September und Dezember (Sonderausgabe nach Bedarf)

Format

210 x 297 mm (DIN A 4)

Bezugspreis

Der Mitgliedsbeitrag beinhaltet den Bezug der VDG-Nachrichten; Bezugspreis für Nichtmitglieder: 13,50 €.

Druck

Karl Elser Druck GmbH, Mühlhacker / E-Mail: info@elserdruck.de

Kontakt, Anfragen und Anzeigenschaltung:

Redaktion des VDG e.V.

c/o Eberhard Karls Universität Tübungen

CZI Glasbläserei

Karin Rein und Thomas Nieß

Auf der Morgenstelle 6

72076 Tübingen